Marburg: What to know about the latest killer virus without a cure yet

MANILA, Philippines—The Marburg virus disease (MVD) is epidemic-prone, the World Health Organization (WHO) said, stressing that it can spread easily if not prevented.

It was last year, Aug. 6, when the Ministry of Health of Guinea reported to WHO about a confirmed MVD case—a male who had fever, headache, fatigue, abdominal pain and gingival hemorrhage.

READ: Guinea records West Africa’s first Marburg virus death, WHO says

The patient, which is the first known case of the disease in Guinea and West Africa, died on Aug. 2, seven days since he started having symptoms, prompting the public health care facility to ask Guéckédou’s prefectorial health department to investigate.

WHO and Guinea’s Ministry of Health then collected a post-mortem oral swab sample. A real-time PCR was conducted and it was confirmed that it was positive for MVD and negative for Ebola virus disease (EVD).

RELATED STORY: 8 things to know about the deadly Ebola virus

Because of the confirmation, the Guinean Ministry of Health, WHO, United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US CDC), Alima, Red Cross, and United Nations Children’s Fund immediately initiated measures to control the outbreak.

The Philippines’ Department of Health (DOH) said then that “as of now, the threat to us, and the risk is very low,” stressing that while there is a possibility of the disease reaching the country, “we would like to guard our borders again and we would like to be very careful on this.”

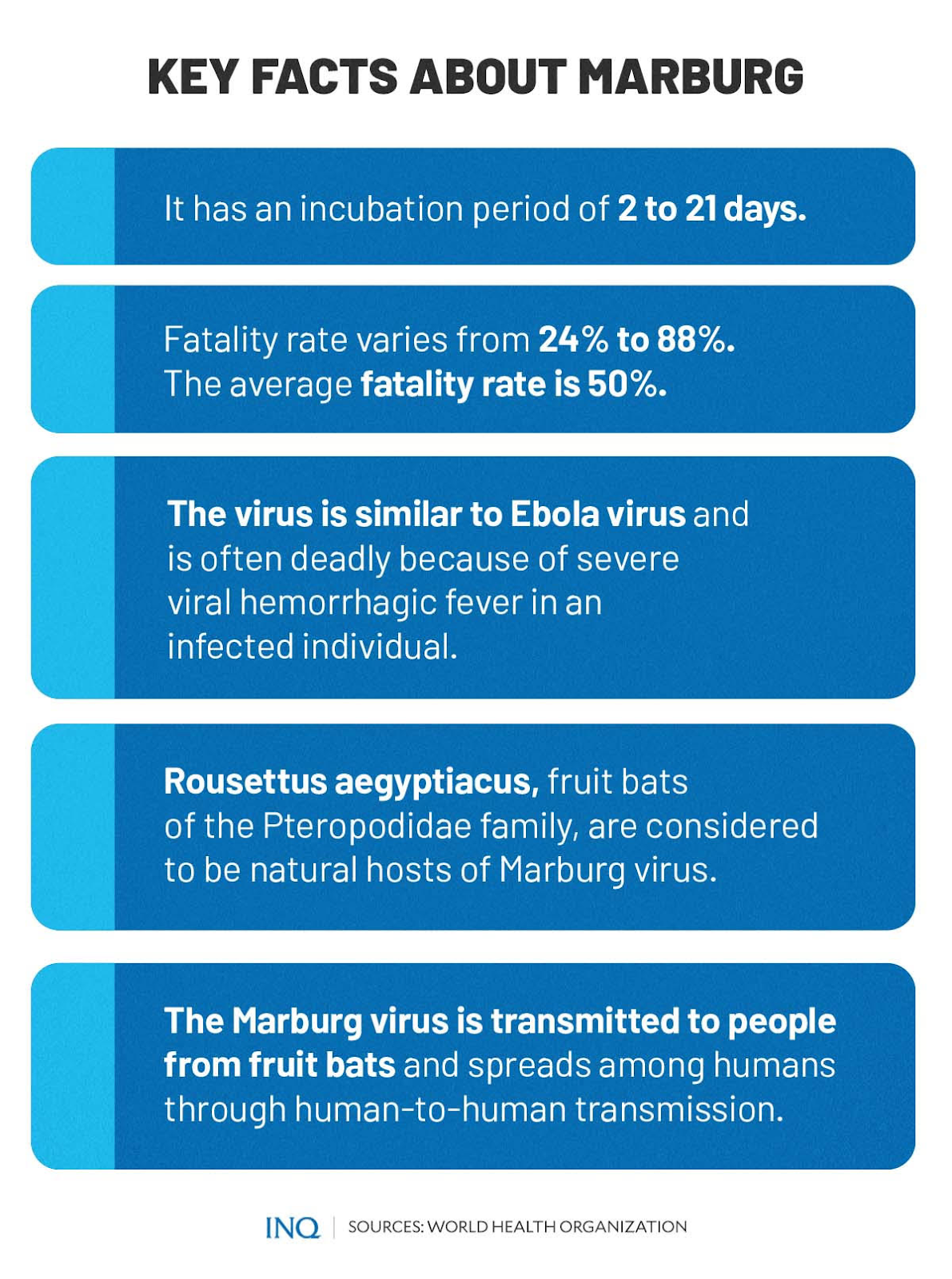

This, as MVD, which was previously known as Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever, was confirmed to be a severe disease and is often deadly as it causes severe viral hemorrhagic fever in an infected individual.

New outbreak

Almost a year since the confirmation of Guinea’s first MVD case, Ghana officially confirmed two cases of the disease as two individuals, who later died, tested positive for the virus earlier this month.

The tests conducted by Ghana came back positive on July 10, however, WHO said the results had to be sent to a laboratory in Senegal for verification. The Institut Pasteur in Dakar, Senegal corroborated the results.

READ: Ghana confirms its first outbreak of highly infectious Marburg virus

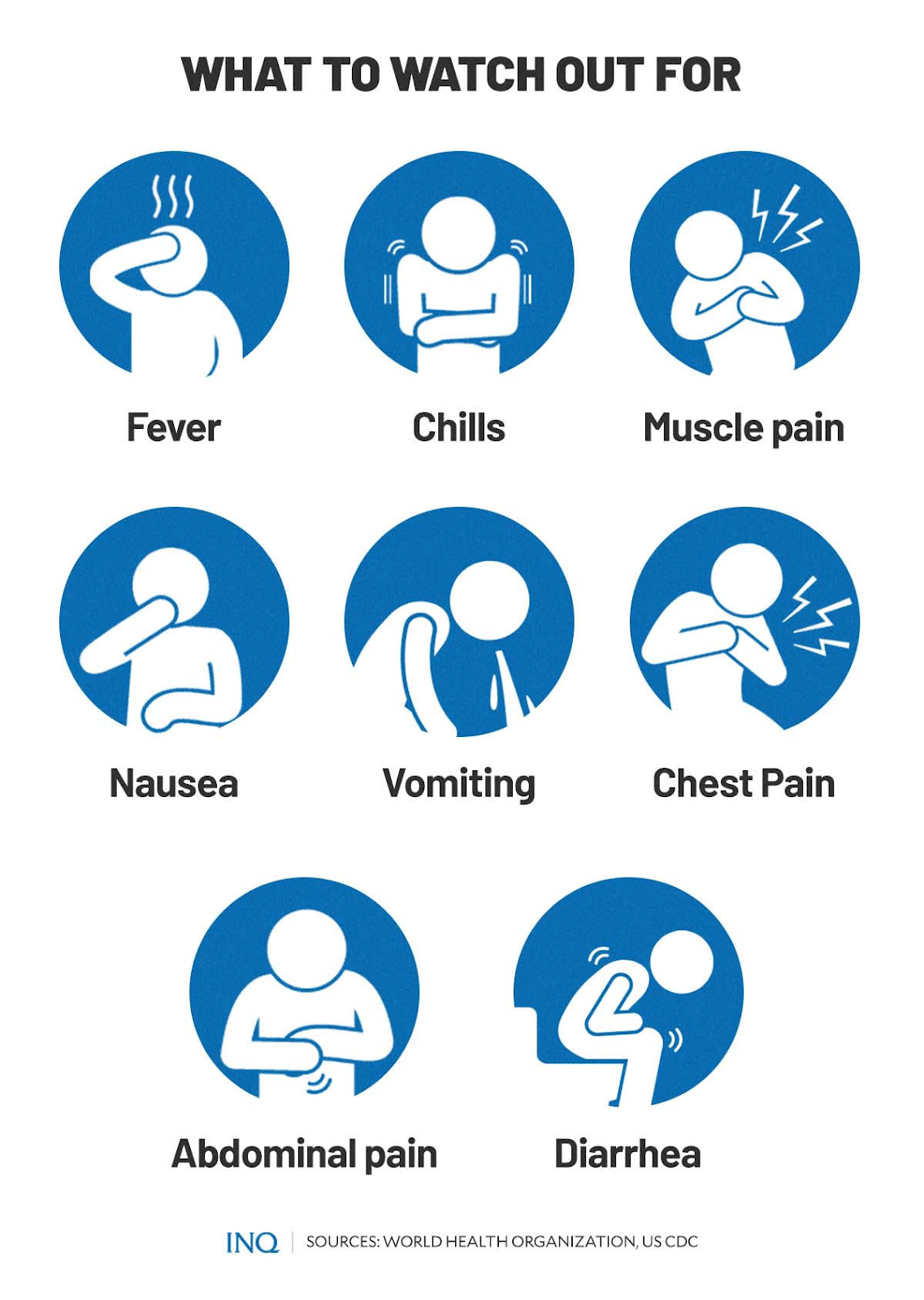

WHO said the patients, who were from southern Ghana’s Ashanti region, both had symptoms, including diarrhea, fever, nausea and vomiting before dying in the hospital.

The Ghana Health Service (GHS) said it is working to mitigate the spread of the virus. All of the 98 identified contacts of the two MVD patients who died are now in isolation, none of whom have developed any MVD symptoms so far.

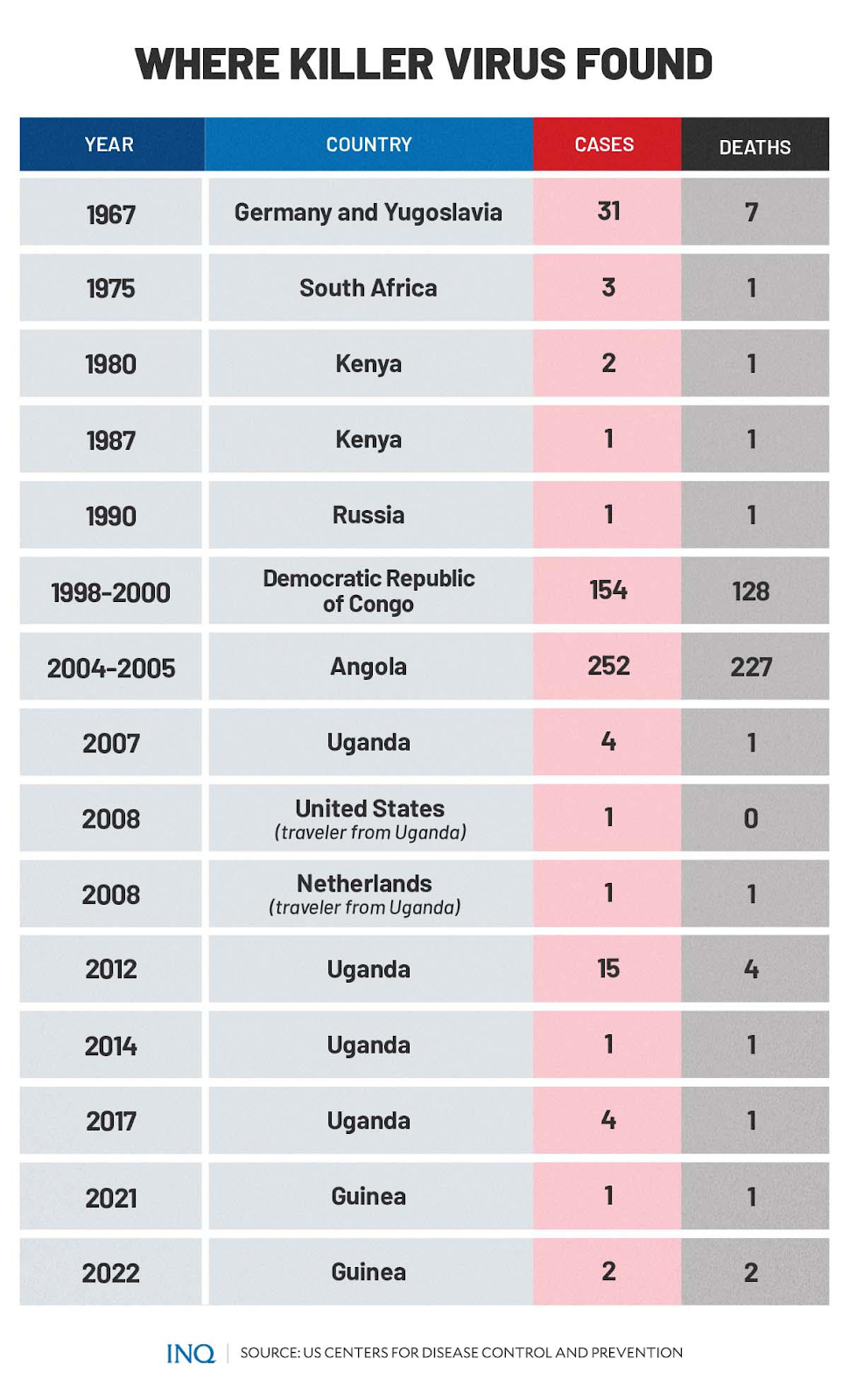

Previous outbreaks have been reported in Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, South Africa, and Uganda. The 2004 to 2005 outbreak in Angola killed 227 people.

Matshidiso Moeti, WHO Regional Director for Africa, said the GHS has responded swiftly, getting a head start preparing for a possible outbreak: “This is good because without immediate and decisive action, Marburg can easily get out of hand.”

The disease

MVD is a “highly virulent disease” that causes hemorrhagic fever. Two large outbreaks that happened simultaneously in Marburg and Frankfurt in Germany, and in Belgrade, Serbia, in 1967, led to the initial recognition of the disease.

WHO said the Marburg virus is in the same family as the virus that causes EVD and that the fatality rate has varied from 24 to 88 percent, depending on the virus strain and case management.

RELATED STORY: DOH gives tips on how Filipinos can avoid Ebola virus

The outbreak then was linked with laboratory work using African green monkey (Cercopithecus aethiops) imported from Uganda. In 2008, the virus was detected in two travelers who visited a cave inhabited by Rousettus bat colonies in Uganda.

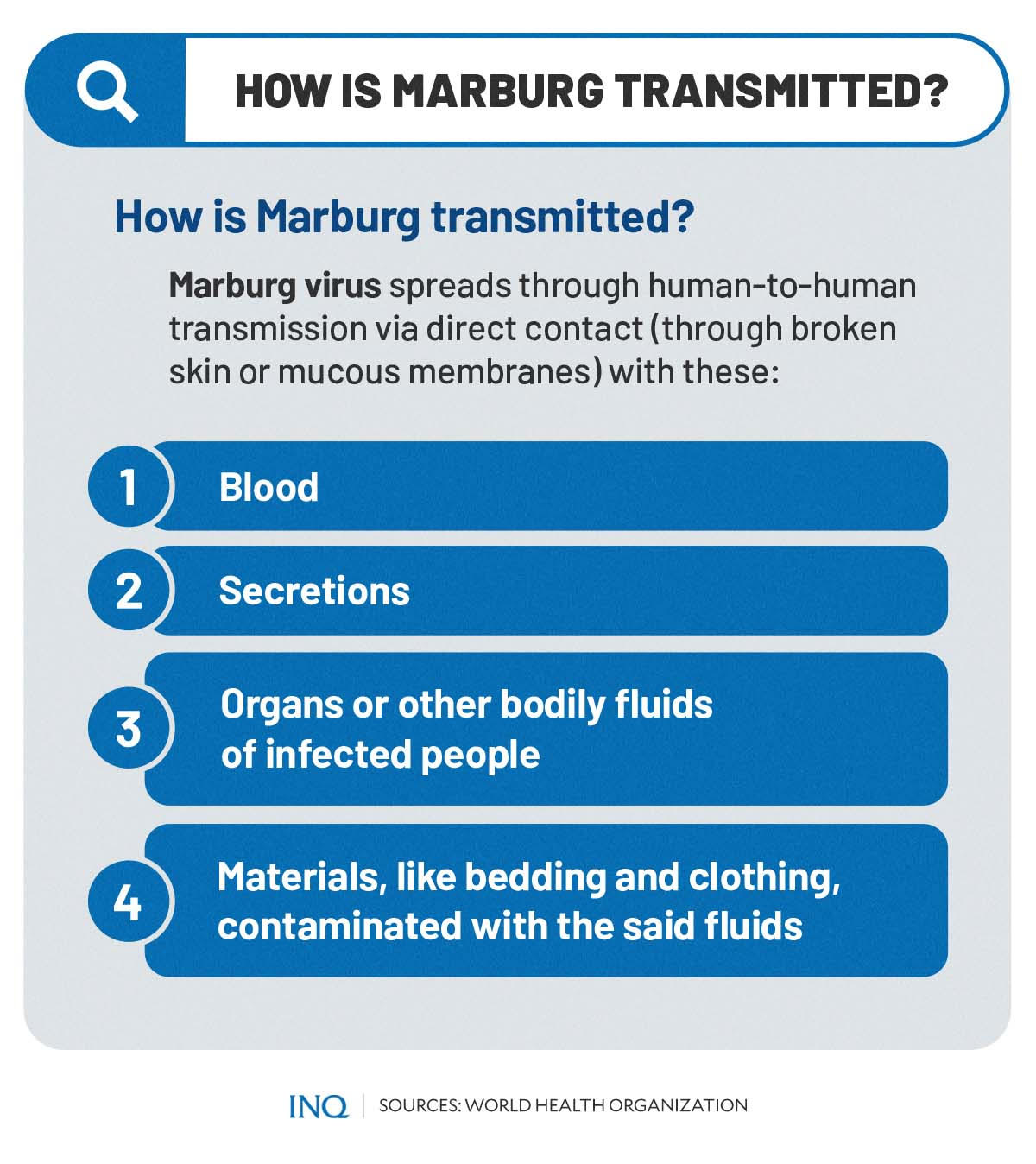

An infection with MVD initially results from prolonged exposure to mines or caves inhabited by Rousettus bat colonies and once an individual is infected with the virus, MVD can spread through direct contact with these:

- Blood of infected people

- Secretions of infected people

- Organs or other bodily fluids of infected people

- Materials, like bedding and clothing, contaminated with the said fluids

Rousettus aegyptiacus, fruit bats of the Pteropodidae family, are considered to be natural hosts of the virus, which is transmitted to people. “People remain infectious as long as their blood contains the virus,” the WHO said.

It stressed that health care workers have often been infected while treating patients with suspected or confirmed MVD. This has occurred through close contact with patients when infection control precautions are not strictly practiced.

WHO said the MVD has an incubation period of two to 21 days and that symptoms are marked by fever, chills, and muscle pains. The CDC said that after the start of symptoms, a rash most prominent on the chest, back and stomach could come out.

The illness caused by the virus “begins abruptly” with high fever, severe headache and severe malaise. Muscle pains are a common feature while severe watery diarrhea, abdominal pain and cramping, nausea and vomiting can begin on the third day.

“The appearance of patients at this phase has been described as showing ‘ghost-like’ drawn features, deep-set eyes, expressionless faces, and extreme lethargy,” WHO said.

Deadly virus

While MVD is “rare,” WHO said it has the capacity to cause outbreaks with a high fatality rate. Many patients develop severe hemorrhagic manifestations between five and seven days, and fatal cases usually have some form of bleeding.

“Fresh blood in vomits and feces is often accompanied by bleeding from the nose, gums, and vagina. Spontaneous bleeding at venipuncture sites can be particularly troublesome,” it said.

WHO explained that in the severe phase of illness, patients have sustained high fevers and that they might likewise show confusion, irritability and aggression. In fatal cases, a patient could die most often between days eight and nine after the onset of symptoms.

Based on data from the CDC, from 1967 to 2021, there have been 417 confirmed MVD cases and 377 deaths. In Angola, out of 252 cases, 227 had died, bringing the fatality rate to 90 percent:

- 1967, Germany and Yugoslavia: 31 cases, 7 deaths

- 1975, South Africa: 3 cases, 1 death

- 1980, Kenya: 2 cases, 1 death

- 1987, Kenya: 1 case, 1 death

- 1990, Russia: 1 case, 1 death

- 1998 to 2000, Democratic Republic of Congo: 154 cases, 128 deaths

- 2004 to 2005, Angola: 252 cases, 227 deaths

- 2007, Uganda: 4 cases, 1 death

- 2008, US (traveler from Uganda): 1 case, 0 death

- 2008, Netherlands (traveler from Uganda): 1 case, 1 death

- 2012, Uganda: 15 cases, 4 deaths

- 2014, Uganda: 1 case, 1 death

- 2017, Uganda: 4 cases, 1 death

- 2021, Guinea: 1 case, 1 death

- 2022, Ghana: 2 cases, 2 deaths

WHO said it can be difficult to clinically distinguish MVD from other infectious diseases such as malaria, typhoid fever, shigellosis, meningitis and other viral hemorrhagic fevers.

Confirmation that symptoms are caused by the virus infection are made using these diagnostic methods:

- Antibody-capture enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay

- Antigen-capture detection tests

- Serum neutralization test

- Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) Assay

- Electron microscopy

- Virus isolation by cell culture

“Samples collected from patients are an extreme biohazard risk; laboratory testing on non-inactivated samples should be conducted under maximum biological containment conditions,” it said.

Is it treatable?

Presently, there are no vaccines or antiviral treatments approved for MVD, WHO said. However, supportive care and treatment of specific symptoms improves survival rates.

“Early supportive care with rehydration, and symptomatic treatment improves survival. There is as yet no licensed treatment proven to neutralize the virus, but a range of blood products, immune therapies and drug therapies are currently under development.”

There are monoclonal antibodies under development and antivirals, like remdesivir and favipiravir that have been used in clinical studies for EVD that could also be tested for MVD or used under compassionate use or expanded access, WHO said.

It was stressed that a good outbreak control relies on using a range of interventions, namely case management, surveillance and contact tracing, a good laboratory service, safe and dignified burials, and social mobilization.

“Community engagement is key to successfully controlling outbreaks. Raising awareness of risk factors for Marburg infection and protective measures that individuals can take is an effective way to reduce human transmission,” WHO said.