WHO’s pandemic treaty and its promise of equity

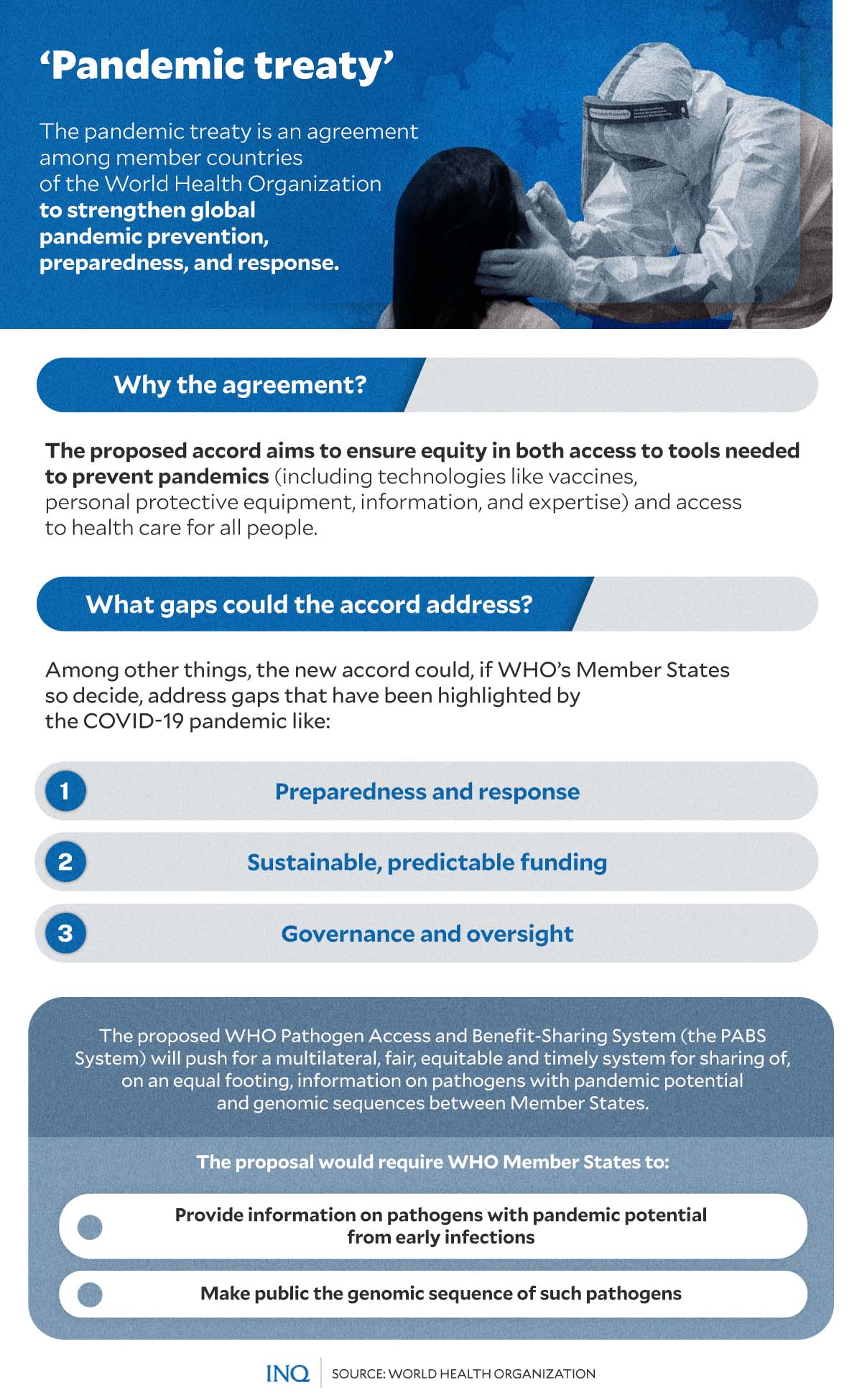

MANILA, Philippines—In an effort to prevent a repeat of failures in the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic, member states of the World Health Organization (WHO) have decided to draft and negotiate a treaty to strengthen pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response.

The COVID-19 pandemic has put in focus the reality of inequities in population morbidity, mortality, and access to medicines, vaccines, and other crucial equipment between nations—especially between rich and poor countries.

Acknowledging failures in the global COVID-19 response and understanding that nations must do better when the next pandemic comes, WHO in December 2021 established an Intergovernmental negotiating body (INB) to come up with a pandemic preparedness agreement.

The treaty “was driven by the need to ensure communities, governments, and all sectors of society—within countries and globally—are better prepared and protected, in order to prevent and respond to future pandemics,” according to WHO.

“The great loss of human life, disruption to households and societies at large, and impact on development are among the factors cited by governments to support the need for lasting action to prevent a repeat of such crises,” WHO explained.

WHO also stressed that at the heart of the proposed accord is

the need to address inequity and ensure equity in both access to tools needed to prevent pandemics—including technologies like vaccines, personal protective equipment, information and expertise—and access to health care for all people.

On February 1, 2023, the first public draft of the accord or the WHO CA+, titled the Zero Draft (ZD), was released. It is the basis for negotiations by the 194 member countries before a draft accord is presented to the World Health Assembly in May 2024.

According to the Council of the European Union, the pandemic accord would support and focus on:

- early detection and prevention of pandemics

- resilience to future pandemics

- response to any future pandemics, in particular by ensuring universal and equitable access to medical solutions, such as vaccines, medicines, and diagnostics

- a more robust international health framework with WHO as the coordinating authority on global health matters.

“More specifically, such an instrument can enhance international cooperation in a number of priority areas, such as surveillance, alerts and response, but also in general trust in the international health system,” the European Council added.

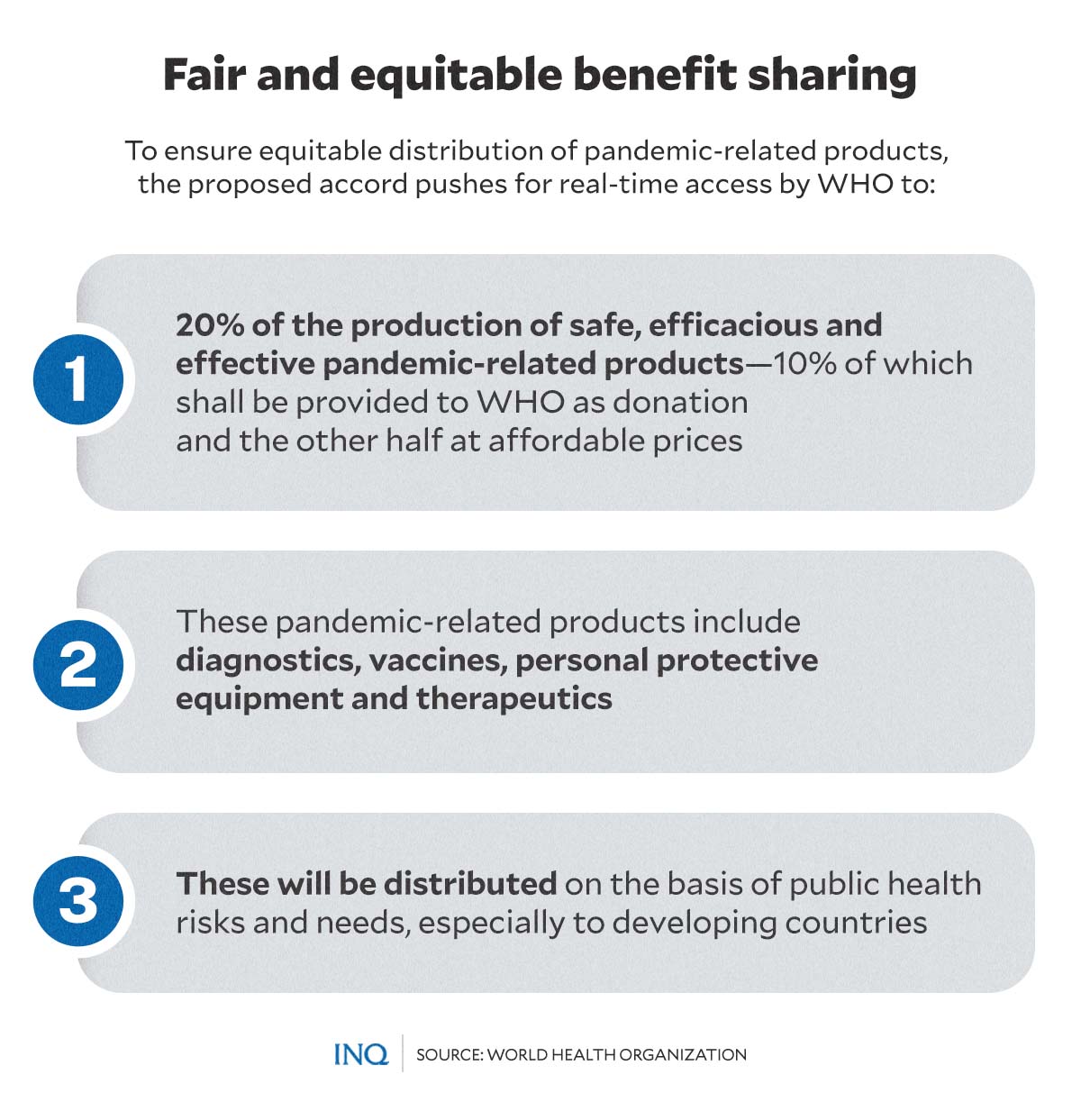

‘Fair and equitable benefit sharing’

“During the COVID-19 pandemic, wealthy nations have been hoarding supplies of vaccines, diagnostic devices, and personal protective equipment, to the detriment of less wealthy nations,” an editorial piece published by The Lancet Global Health noted.

In an analysis by the UN Development Program (UNDP) released in March last year, the UN said that while the number of vaccines administered worldwide has risen “dramatically,” so did inequity in vaccine distribution.

The organization stressed that out of the over 10 billion doses given out worldwide, only one percent had been administered in low-income countries. These included vulnerable countries found in Sub-Saharan Africa.

“Vaccine inequity jeopardizes the safety of everyone and contributes to growing inequalities between—and within—countries,” the UNDP explained.

“Not only does this state of affairs risk prolonging the pandemic, but the lack of equity has many other impacts, slowing the economic recovery of entire countries, global labor markets, public debt payments, and countries’ ability to invest in other priorities,” it added.

Acknowledging inequity during the COVID-19 pandemic is one of the main issues the WHO CA+ or the pandemic treaty aims to address—with strong emphasis on achieving equity in future responses.

Article 10 of the proposed accord states that WHO should have access to 20 percent of pandemic-related products—including diagnostics, vaccines, personal protective equipment, and therapeutics—which will be equally distributed to priority populations.

Half of that 20 percent should be provided to WHO free of charge, while the other 10 percent should be provided at “affordable prices.”

Another option for fair and equitable benefit-sharing, as stated in Article 10 of the proposed treaty, is the “commitments by the countries where manufacturing facilities are located that they will facilitate the shipment to WHO of these pandemic-related products by the manufacturers within their jurisdiction, according to schedules to be agreed between WHO and manufacturers.”

However, The Lancet Global Health pointed out that it still needs to be clarified which countries should provide these products to the WHO.

“COVID-19 showed that capitalism, well suited to protect shareholder dividends, was ineffective at optimum vaccine distribution. It remains to be seen whether all private companies will balance social responsibility with profit generation when supplying the non-donated 10%,” the editorial said.

Viral-genome data sharing

Another vital part of the pandemic treaty is sharing viral-genome data between nations.

According to the European Council, sharing such information—which includes pathogens, biological samples, and genomic data—and the development of medical solutions such as vaccines, treatments, and diagnostics are crucial in enhancing global pandemic preparedness.

In Article 10 of the Zero Draft, nations are required to “provide pathogens with pandemic potential from early infections due to pathogens with pandemic potential or subsequent variants to a laboratory recognized or designated as part of an established WHO coordinated laboratory network” in a rapid, systematic, and timely matter.

Nations are also asked to “upload the genomic sequence of such pathogens with the pandemic potential to one or more publicly accessible databases of its choice.”

The draft emphasized that this information must be shared and submitted within hours from the time of identification of a pathogen with pandemic potential.

However, several concerns regarding sharing pathogen data have been voiced, especially among many low- and middle-income countries.

“We are all quite concerned about protecting the sovereign right to control access to genetic resources, and not giving that up without at least getting something substantial in return,” said Pierre du Plessis, one of Africa’s lead negotiators on genetic resources, in an article published by Nature journal.

During the pandemic, South Africa was among the nations that kept tabs on the SARS-CoV-2 virus and its mutations. Its researchers have uploaded genetic sequences of the virus to online-data sharing platforms, which helped develop vaccines against the disease.

However, despite their massive contribution, countries like South Africa and others that have uploaded research and data on genetic sequences of the virus experienced a slow rollout of vaccine shots due to supply shortages.

What went before

Concerns about countries refusing to share their genome data are not new.

In 2007, during the outbreak of the H5N1 avian influenza virus, Indonesian officials refused to share crucial bird flu samples with the WHO citing repeated violations of UN guidelines on sample sharing.

In an article published in an issue of The Annals, Academy of Medicine, Singapore, Indonesian scientists and officials were quoted as saying that the then system of sample sharing was unfair and has led to the “inequities of the global system.”

Indonesian officials likewise called for “efforts to create a mechanism for virus access and benefit sharing that is accepted by all nations.”

Those statements came after Indonesian officials discovered that an Australian company was developing a vaccine against the H5N1 bird flu virus in 2006 using a strain of virus from Indonesia.

The officials, citing WHO rules, argued that the viruses and specimens shared by nations should not be distributed outside the network of WHO laboratories without permission from country or lab of origin.

They added that then-system of sample sharing enables companies in rich countries to develop drugs using samples provided freely by developing states—the same poorer nations that would probably struggle to afford such products.

“Countries that are hardest hit by a disease must also bear the burden of the cost for vaccine, therapeutics and other products, while the monetary and non-monetary benefits of these products go to the manufacturers that are mostly in the industrialized countries,” the article stated.

“If the world continues to operate in this way, the discrepancies will become wider and wider. The poor will become poorer and the rich become richer.”

This move by Indonesian officials to withhold samples as a way of protesting what it claims was an unfair system has eventually led to the development of the Pandemic Influenza Preparedness Framework.

WHO stressed that the framework was created “with the objective of a fair, transparent, equitable, efficient, effective system for, on an equal footing:

- the sharing of H5N1 and other influenza viruses with human pandemic potential; and

- access to vaccines and sharing of other benefits.”

However, the ground rules set under the framework apply only to influenza viruses.

A step forward?

While negotiations are underway on the proposed pandemic treaty, and despite criticisms and concerns about the accord, some have already expressed optimistic views on how it can benefit countries in the future.

“The draft WHO CA+ represents a genuinely positive step towards a more equitable pandemic response relative to the COVID-19 pandemic,” The Lancet Global Health noted.

“The INB must ensure that equity remains prominent in the final draft and that the issue of accountability is not left to a nebulous future body or negotiation process.”

An essay published by Harvard Public Health meanwhile stressed that the pandemic treaty might “spark a global health revolution’ and make significant changes in the current system, in which “money, not health, is driving decision-making around the globe.”

“When the next pandemic washes ashore, the best solution is to make sure each continent has the capacity to manufacture and supply its own needs without being left to the charity of wealthy nations,” Vidya Krishnan, a journalist based in India, wrote.

“The new pandemic treaty, if adopted, may help prevent future pandemics from wreaking havoc in low-income countries, and accelerate new treatments and vaccines for existing ones like tuberculosis,” she continued.

“The new reality is that a global response cannot be built around donations, charity, or the largesse of billionaires. The fire of revolution has been lit. And fortunately for us, like plagues, radical ideas are infectious, too.”

TSB

RELATED STORIES:

Explainer: How the World Health Organization could fight future pandemics

WHO reaches draft consensus on future pandemic treaty